Best-known for his illustrations of Charles Dickens's works, George Cruikshank worked as a caricaturist and illustrator, becoming the most celebrated satirical artist of his day. The Museum of London holds a collection of over three hundred prints of his work and a few original drawings.

George was, in his own words, 'cradled in caricature', being trained in the art by his father Isaac Cruikshank (1764-1811) and frequently collaborating with him and his brother Isaac Robert (1789-1856). As a young man he had hoped to go to sea like Robert, but reluctantly agreed to stay in the studio and work with his father. By 1803 he was supplying simple designs to wood-engravers for children's games and books, and went on to produce designs for a wide range of printed material. His earliest broadside satires, signed as 'G. Cruikshank' were in 1808. He took over the family business upon the death of his father in 1811, and was soon famous.

He became well-known for his caricatures of Napoleon, inventing numerous ways of lampooning the French leader, but also mocked George IV and his court, political figures, fashionable types, famous figures and contemporary crazes. From 1815 his principal collaborated was the antiquarian book dealer and radical publisher William Hone.

In the 1820s Cruikshank moved into book illustration. With his brother Robert he illustrated Pierce Egan's Life in London (1820-21), before illustrating an English translation of the Grimms' fairy tales (1823-6). From 1826 he issued his own albums of prints with comic depictions of contemporary scenes, characters and fads: Phrenological Illustrations (1826), Illustrations of Time (1827), Scraps and Sketches (four series, 1828-32), My Sketch Book (nine parts, 1833-36), and Cruikshank's Comic Almanack (1835-53).

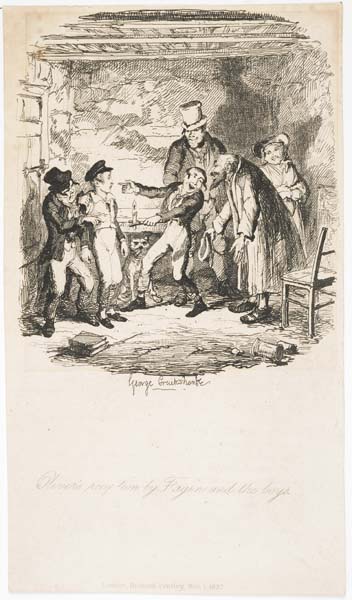

In 1835 Cruikshank began working with Charles Dickens on the latter's Sketches by Boz (1836), and then on Bentley's Miscellany (1837-43), in which Oliver Twist and Ainsworth's Jack Sheppard were both published with illustrations by Cruikshank.

By the late 1840s his career had started to falter as, despite his fame, he began to receive fewer and less profitable commissions. He continued to initiate many of his own projects, but these were often financially misjudged. His increasing interest in the temperance cause worsened his financial worries as his polemics – including The Bottle (1847) and The Drunkard’s Children (1848) – sold badly, and he expended a large among of time on a vast oil painting, The Worship of Bacchus (1862, Tate). His commitment to the cause also marked him out as something of an eccentric. His money troubles were much compounded by the costs of supporting his sister, his mother, a sickly first wife, and then, along with his second wife, a secret second family. He continued to work, however, and among the highlights of his later productions are a series of satires of visitors to the Great Exhibition (1851).